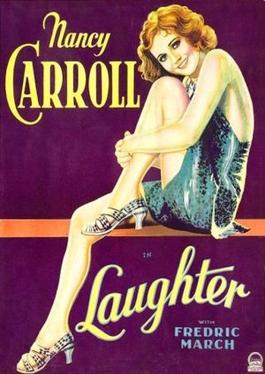

| Laughter (film) (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

* Okay, occasionally I'll watch a sitcom to see "what the young people are thinking." Does Master of None tell me what you're thinking?

* I think the Superiority Theory of comedy is useful in thinking about sitcoms. Laughter is judgment. I am better than you, sitcom character! But is this an individual superiority or a categorical superiority? Who or what is being judged? Am I rejecting a category of behavior - let's say vanity - and thus being educated or improved. Or am I being encouraged to use laughter to exclude and demean - a gender, an ethnicity, a sexual preference? Laughter restores order. In emphasizes norms. It is a social corrective. Thus, sometimes laughter inevitably shades into bigotry, which happens most often when sitcoms lack diversity of all kinds, where there is structural exclusion in that a foolish "purple" character is not counterbalanced by a normal "purple" character. Here's a block quote from English professor James Kincaid:

We must deal with "the

degree to which laughter expresses (if it does at all) hostility, aggression, the vestiges of the jungle whoop of triumph after murder, and other unpleasant

impulses. The corollary to this issue is the debate over whether laughter is

incompatible with sympathy, geniality, or indeed with any emotion.... Nearly all the important writers on the subject

have, for hundreds of years, noted "a component of malice, of

debasement of the other fellow, and of aggressive-defensive self-assertion . .

. in laughter -- a tendency diametrically opposed to sympathy, helpfulness, and

identification of the self with others" I find this argument ... conclusive.

* An alternative theory to humor as contempt exists! That's the "genial laughter theory," that laughter sometimes is simply a matter of acknowledging the general foolishness and absurdity of human life, that laughter does not cause us to exclude but to accept others, to see us in them. It is certainly true that many sitcoms have what I call "soft landings" for characters. The character we are invited to laugh at then does something "unfoolish." Or another character accepts and forgives the foolish character, modeling how we should behave. In other words, not all sitcoms are funny all the time, and we have to be attentive to how the serious moments soften the comic ones. Even if we are invited to feel contempt, we may be discouraged from feeling it all the time.

* Of course, some of the most interesting sitcoms are those where it seems we are never ask to sympathize with a character or characters. They are "dark." This may fit with the idea that a sitcom is a mirror not only reflecting society as a whole but us, the individual viewer. If "dark" comedy is designed to make us experience both laughter and discomfort at the same time, what does that tell us about us? Here's a list of "wonderfully dark sitcoms." Also, there is the category of black comedy, or gallows humor, which some would define as having the courage to laugh in the face of disaster to keep up our spirits. "Black humor, in literature, drama, and film, grotesque or morbid humor used to express the absurdity, insensitivity, paradox, and cruelty of the modern world." - Columbia Encyclopedia "And if I laugh at any mortal thing, 'tis that I may not weep." - George Noel Gordon, Lord Byron

* A simple way of looking at sitcom: Incongruity as the source of humor. That works no matter what your umbrella theory of the uses and effects of humor are. Absurdity, exaggeration, hyperbole, abrupt change. Often humor really does seem to be a simple matter of reversed expectations.

* The power of the unconscious. Laughter seems automatic. If you decide to **think** while watching, probably taking advantage of the ability to rewind and rewatch, not just episodes but single moments, such self scrutiny can be uncomfortable. Freud says - I oversimplify here - that in the service of living in civilization we mash down certain cruel and/or sexual and/or antisocial feelings into our unconscious. Laughter can be a way of releasing some of the tension such repression creates. Think about how taboo - sexual references, certain obscenities vigorously said - can produce laughter. It is as if humor suddenly gives us permission, particularly as a member of a crowd, to express that which we otherwise keep hidden.

* One final point from Kincaid because I like his examples. Comedy can leave us vulnerable. Have you ever stumbled across some obscure movie on Netflix - possibly foreign with subtitles! - that you watch with unease because context does not make clear what the genre is. Kincaid:

Having released the energies ordinarily used to guard

our hostilities, inhibitions, or fears, we are especially unprotected if the

promised safety which allowed us to laugh proves to be illusory. Imagine the

fat old man who slipped on the banana peel being suddenly identified as our

brother, now seriously hurt; the custard pie containing sulphuric acid; the

train really hitting the funny car and killing the Keystone Cops.

* All that said, it's possible some sitcoms make us better people. Effects research is always tricky.

* All that said, it's possible some sitcoms make us better people. Effects research is always tricky.

No comments:

Post a Comment