Welcome to the web

log of the L.A. Stuckist group. We are Remodernists seeking the renewal of

spirituality and meaning in art, culture and society. We wish to build an

international art movement for new figurative painting with ideas. We stand

against the pretensions of conceptual art - we are anti anti-art. www.la-stuckism.com

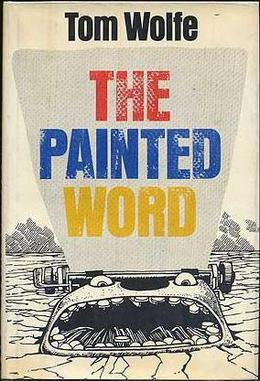

American author and journalist, Thomas Wolfe, is certainly one of the country’s

best writers. Over the decades he’s penned works as diverse as The Electric

Kool-Aid Acid Test, The Right Stuff, and The Bonfire of the

Vanities. He also wrote two extremely controversial histories regarding

modern art and architecture, The Painted Word (1975) and From

Bauhaus To Our House (1981). Despite Wolfe’s conservatism, it’s hard to

imagine the critique contained in his essays on art as coming from your average

garden variety reactionary. Wolfe’s critical assessment of modern art, and his

ridiculing those who defended its excesses, seems wholly prescient when viewed

from today’s vantage point. If anything, the extremes in art lambasted by Wolfe

have subsequently become worse as postmodernism ascended and took center stage.

In

The Painted Word, Wolfe began his essay by recounting a

revelatory experience he had on April 28, 1974, while reading an art review by

Hilton Kramer for the New York Times. Kramer, a leading proponent of abstract

art, had written: "Realism does not lack its partisans, but it does rather

conspicuously lack a persuasive theory" - a statement that provoked Wolfe

to write:

"PEOPLE DON'T READ the morning

newspaper, Marshall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. Too

true, Marshall! Imagine being in New York City on the morning of Sunday, April

28, 1974, like I was, slipping into that great public bath, that vat, that spa,

that regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad,

that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls which is the Sunday New York

Times. Soon I was submerged, weightless, suspended in the tepid depths of the

thing, in Arts & Leisure, Section 2, page 19, in a state of perfect sensory

deprivation, when all at once an extraordinary thing happened:

I noticed something!

Yet another clam-broth-colored current

had begun to roll over me, as warm and predictable as the Gulf Stream . . . a

review, it was, by the Times's dean of the arts, Hilton Kramer, of an

exhibition at Yale University of "Seven Realists," seven realistic

painters . . . when I was jerked alert by the following:

"Realism does not lack its

partisans, but it does rather conspicuously lack a persuasive theory. And given

the nature of our intellectual commerce with works, of art, to lack a

persuasive theory is to lack something crucial—the means by which our

experience of individual works is joined to our understanding of the values

they signify."

Now, you may say, My God, man! You

woke up over that? You forsook your blissful coma over a mere swell in the sea

of words?

But I knew what I was looking at. I

realized that without making the slightest effort I had come upon one of those

utterances in search of which psychoanalysts and State Department monitors of

the Moscow or Belgrade pres are willing to endure a lifetime of tedium: namely,

the seemingly innocuous obiter dicta, the words in passing, that give the game

away.

What I saw before me was the

critic-in-chief of The New York Times saying: In looking at a painting today,

"to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial." I read it

again. It didn't say "something helpful" or "enriching" or

even "extremely valuable." No, the word was crucial.

In short: frankly, these days, without

a theory to go with it, I can't see a painting.

Then and there I experienced a flash

known as the Aha! Phenomenon, and the buried life of contemporary art was

revealed to me for the first time. The fogs lifted! The clouds passed! The

motes, scales, conjunctival bloodshot, and Murine agonies fell away!

All these years, along with countless

kindred souls, I am certain, I had made my way into the galleries of Upper

Madison and Lower Soho and the Art Gildo Midway of Fifty-seventh Street, and

into the museums, into the Modern, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim, the Bastard

Bauhaus, the New Brutalist, and the Fountainhead Baroque, into the lowliest

storefront churches and grandest Robber Baronial temples of Modernism.

All these years I, like so many

others, had stood in front of a thousand, two thousand, God-knows-how-many

thousand Pollocks, de Koonings, Newmans, Nolands, Rothkos, Rauschenbergs,

Judds, Johnses, Olitskis, Louises, Stills, Franz Klines, Frankenthalers,

Kellys, and Frank Stellas, now squinting, now popping the eye sockets open, now

drawing back, now moving closer - waiting, waiting, forever waiting for… it…

for it to come into focus, namely, the visual reward (for so much effort) which

must be there, which everyone (tout le monde) knew to be there - waiting for

something to radiate directly from the paintings on these invariably pure white

walls, in this room, in this moment, into my own optic chiasma.

All these years, in short, I had

assumed that in art, if nowhere else, seeing is believing. Well - how very

shortsighted! Now, at last, on April 28, 1974, I could see. I had gotten it backward

all along. Not 'seeing is believing,' you ninny, but 'believing is seeing,' for

Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist

only to illustrate the text."

And what was the "text" he spoke of? Wolfe asserted that the

critics, museum directors, academics, and other "art experts" of the

day, had become more important than the artists. These art authorities began

operating like the clergy, but their religious duties were to the church of

modern art. The proclamations of these high priests - i.e., figuration,

narration, and realism in art was archaic and passé - became a divine text and

considered the sacred word. No one dared to question the word for fear of being

thought heretical. Metaphorically, the painted word began to appear in the work

of artists devoted to the new orthodoxy (hence the title of the essay). Wolfe

foretold our current predicament when he wrote:

"Every art student will marvel

over the fact that a whole generation of artists devoted their careers to getting

the Word (and to internalizing it) and to the extraordinary task of divesting

themselves of whatever there was in their imagination and technical ability

that did not fit the Word. They will listen to art historians say, with the

sort of smile now reserved for the study of Phrygian astrology: 'That’s how it

was then!' - as they describe how, on the one hand, the scientists of the

mid-twentieth century proceeded by building upon the discoveries of their

predecessors and thereby lit up the sky… while the artists proceeded by

averting their eyes from whatever their predecessors, from da Vinci on, had

discovered, shrinking from it, terrified, or disintegrating it with the

universal solvent of the Word.

The more industrious scholars will

derive considerable pleasure from describing how the art-history professors and

journalists of the period 1945-75, along with so many students, intellectuals,

and art tourists of every sort, actually struggled to see the paintings

directly, in the old pre-World War II way, like Plato’s cave dwellers watching

the shadows, without knowing what had projected them, which was the Word.What

happy hours await them all! With what sniggers, laughter, and good-humored

amazement they will look back upon the era of the Painted Word!"

[ Read more excerpts from Thomas Wolfe’s

The Painted Word, or

purchase the entire book from Amazon.com ]

Chapter One The Apache Dance

ALL THE MAJOR MODERN MOVEMENTS EXCEPT FOR DE STIJL, Dada, Constructivism,

and Surrealism began before the First World War, and yet they all seem to come

out of the 1920s. Why? Because it was in the 1920s that Modern Art achieved

social chic in Paris, London, Berlin, and New York. Smart people talked about

it, wrote about it, enthused over it, and borrowed from it. Borrowed from it,

as I say; Modern Art achieved the ultimate social acceptance: interior

decorators did knock-offs of it in Belgravia and the sixteenth arrondissement.

Things like knock-off specialists, money, publicity, the smart set, and Le

Chic shouldnt count in the history of art, as we all knowbut, thanks to the

artists themselves, they do. Art and fashion are a two-backed beast today; the

artists can yell at fashion, but they cant move out ahead. That has come about

as follows:

By 1900 the artists arena, the place where he seeks honor, glory, ease,

Success had shifted twice. In seventeenth century Europe the artist was

literally, and also psychologically, the house guest of the nobility and the

royal court (except in Holland); fine art and court art were one and the same.

In the eighteenth century the scene shifted to the salons, in the homes of the

wealthy bourgeoisie as well as those of aristocrats, where Culture-minded

members of the upper classes held regular meetings with selected artists and

writers. The artist was still the Gentleman, not yet the Genius. After the

French Revolution, artists began to leave the salons and join cénacles, which

were fraternities of like-minded souls huddled at some place like the Café

Guerdons rather than a town house; around some romantic figure, an artist

rather than a socialite, someone like Victor Hugo, Charles Nosier, Théophile

Gautier, or, later, Edouard Manet. What held the cénacles together was that

merry battle spirit we have all come to know and love: épatez la bourgeoisie,

shock the middle class. With Gautiers cénacle especially . . . with Gautiers

own red vests, black scarves, crazy hats, outrageous pronouncements, huge

thirsts, and ravenous groin . . . the modern picture of The Artist began to

form: the poor but free spirit, plebeian but aspiring only to be classless, to

cut himself forever free from the bonds of the greedy and hypocritical

bourgeoisie, to be whatever the fat burghers feared most, to cross the line

wherever they drew it, to look at the world in a way they couldnt see, to be

high, live low, stay young foreverin short, to be the bohemian.

By 1900 and the era of Picasso, Braque & Co., the modern game of Success

in Art was pretty well set. As a painter or sculptor the artist would do work

that baffled or subverted the cozy bourgeois vision of reality. As an

individual well, that was a bit more complex. As a bohemian, the artist had now

left the salons of the upper classes but he had not left their world. For

getting away from the bourgeoisie there’s nothing like packing up your paints

and easel and heading for Tahiti, or even Brittany, which was Gauguins first

stop. But who else even got as far as Brittany? Nobody. The rest got no farther

than the heights of Montmartre and Montparnasse, which are what? perhaps two

miles from the Champs Elysées. Likewise in the United States: believe me, you

can get all the tubes of Winsor & Newton paint you want in Cincinnati, but

the artists keep migrating to New York all the same . . . You can see them six

days a week . . . hot off the Carey airport bus, lined up in front of the

real-estate office on Broome Street in their identical blue jeans, gum boots, and quilted Long

March jackets . . . looking, of course, for the inevitable Loft . . .

No, somehow the artist wanted to remain within walking distance . . . He

took up quarters just around the corner from . . . le monde, the social sphere

described so well by Balzac, the milieu of those who find it important to be in

fashion, the orbit of those aristocrats, wealthy bourgeois, publishers,

writers, journalists, impresarios, performers, who wish to be "where

things happen," the glamorous but small world of that creation of the

nineteenth-century metropolis, tout le monde, Everybody, as in "Everybody

says". . . the smart set, in a phrase . . . "smart," with its

overtones of cultivation as well as cynicism.

The ambitious artist, the artist who wanted Success, now had to do a bit of

psychological double-tracking. Consciously he had to dedicate himself to the

antibourgeois values of the cénacles of whatever sort, to bohemia, to the

Bloomsbury life, the Left Bank life, the Lower Broadway Loft life, to the

sacred squalor of it all, to the grim silhouette of the black Reorig Lower

Manhattan truck-route internal combustion granules that were already standing an

eighth of an inch thick on the poisoned roach carcasses atop the electric

hot-plate burner by the time you got up for breakfast . . . Not only that, he

had to dedicate himself to the quirky god Avant-Garde. He had to keep one

devout eye peeled for the new edge on the blade of the wedge of the head on the

latest pick thrust of the newest exploratory probe of this falls avant-garde

Breakthrough of the Century . . . all this in order to make it, to be noticed,

to be counted, within the community of artists themselves. What is more, he had

to be sincere about it. At the same time he had to keep his other eye cocked to

see if anyone in le monde was watching. Have they noticed me yet? Have they

even noticed the new style (that me and my friends are working in)? Dont they

even know about Tensionism (or Slice Art or Niho or Innerism or Dimensional

Creamo or whatever)? (Hello, out there!) . . . because as every artist knew in

his heart of hearts, no matter how many times he tried to close his eyes and

pretend otherwise (History! History!where is thy salve? ), Success was real

only when it was success within lemonde.

He could close his eyes and try to believe that all that mattered was that

he knew his work was great . . . and that other artists respected it . . . and

that History would surely record his achievements . . . but deep down he knew

he was lying to himself. I want to be a Name, goddamn it!at least that, a name,

a name on the lips of the museum curators, gallery owners, collectors, patrons,

board members, committee members, Culture hostesses, and their attendant

intellectuals and journalists and their Time and Newsweek all right!even

that!Time and Newsweek Oh yes! (ask the shades of Jackson Pollock and Mark

Rothko!) even the goddamned journalists!

During the 1960s this entire process by which le monde, the culturati, scout

bohemia and tap the young artist for Success was acted out in the most graphic

way. Early each spring, two emissaries from the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred

Barr and Dorothy Miller, would head downtown from the Museum on West

Fifty-third Street, down to Saint Marks Place, Little Italy, Broome Street and

environs, and tour the loft studios of known artists and unknowns alike,

looking at everything, talking to one and all, trying to get a line on what was

new and significant in order to put together a show in the fall . . . and,

well, I mean, my God from the moment the two of them stepped out on Fifty-third

Street to grab a cab, some sort of boho radar began to record their sortie . .

. They’re coming! . . . And rolling across Lower Manhattan, like the Cosmic

Pulse of the theosophists, would be a unitary heartbeat:

Pick me pick me pick me pick me pick me pick me pick me . . . O damnable

Uptown!

By all means, deny it if asked! what one knows, in ones cheating heart, and

what one says are two different things!

So it was that the art mating ritual developed early in the centuryin Paris,

in Rome, in London, Berlin, Munich,

Vienna, and, not too long afterward, in New York. As weve just seen, the

ritual has two phases:

(1) The Boho Dance, in which the artist shows his stuff within the circles,

coteries, movements, isms, of the home neighborhood, bohemia itself, as if he

doesnt care about anything else; as if, in fact, he has a knife in his teeth

against the fashionable world uptown.

(2) The Consummation, in which culturati from that very same world, le

monde, scout the various new movements and new artists of bohemia, select those

who seem the most exciting, original, important, by whatever standards and

shower them with all the rewards of celebrity.

By the First World War the process was already like what in the Paris clip

joints of the day was known as an apache dance. The artist was like the female

in t he act, stamping her feet, yelling defiance one moment, feigning

indifference the next, resisting the advances of her pursuer with absolute

contempt . . . more thrashing about . . . more rake-a-cheek fury . . . more

yelling and carrying on . . . until finally with one last mighty and

marvelously ambiguous shriekpain! ecstasy! she submits . . . Paff paff paff

paff paff. . . How you do it, my boy! . . . and the house lights rise and

Everyone, tout le monde, applauds . . .

The artists payoff in this ritual is obvious enough. He stands to gain

precisely what Freud says are the goals of the artist: fame, money, and

beautiful lovers. But what about le monde, the culturati, the social members of

the act? What’s in it for them? Part of their reward is t he ancient and

semi-sacred status of Benefactor of the Arts. The arts have always been a

doorway into Society, and in the largest cities today the arts the museum

boards, arts councils, fund drives, openings, parties, committee meetings have

completely replaced the churches in this respect. But there is more!

Today there is a peculiarly modern reward that the avant-garde artist can

give his benefactor: namely, the feeling that he, like his mate the artist, is

separate from and aloof from the bourgeoisie, the middle classes . . . the

feeling that he may be from the middle class but he is no longer in it . . .

the feeling that he is a fellow soldier, or at least an aide-de-camp or an

honorary cong guerrilla in the vanguard march through the land of the

philistines. This is a peculiarly modern need and a peculiarly modern kind of

salvation (from the sin of Too Much Money) and something quite common among the

well-to-do all over the West, in Rome and Milan as well as New York. That is

why collecting contemporary art, the leading edge, the latest thing, warm and

wet from the Loft, appeals specifically to those who feel most uneasy about

their own commercial wealth . . . See? I’m not like them those Jaycees, those

United Fund chairmen, those Young Presidents, those mindless New York A.C.

goyisheh hog-jowled stripe-tied goddamn-good-to-see-you-you-old-bastard- you

oyster-bar trenchermen . . . Avant-garde art, more than any other, takes the

Mammon and the Moloch out of money, puts Levis, turtlenecks, muttonchops, and

other mantles and laurels of bohemian grace upon it.

That is why collectors today not only seek out the company of, but also want

to hang out amidst, lollygag around with, and enter into the milieu of . . .

the artists they patronize. They want to climb those vertiginous loft building

stairs on Howard Street that go up five flights without a single turn or

bendstraight up! like something out of a casebook dreamto wind up with their

hearts ricocheting around in their rib cages with tachycardia from the exertion

mainly but also from the anticipation that just beyond this door at the top . .

. in this loft . . .lie the real goods . . . paintings, sculptures that are

indisputably part of the new movement, the new école, the new wave . .

something unshrinkable, chipsy, pure cong, bourgeois-proof.